Basotho migrants forced to pay bribes for health services in SA

SHARE THIS PAGE!

Migrant Basotho workers in South Africa are reportedly being forced to pay bribes by anti-immigrant groups to access healthcare services, it has emerged.

An association representing the migrants says they are still being denied access to public healthcare facilities for failing to produce SA Identity Documents (IDs), despite bilateral meetings between the two governments. As a result, some have resorted to paying bribes of various amounts in order to receive services, by people believed to be members of Operation Dudula, a xenophobic group that has been blocking entrances to health centres across the neighbouring country since August.

A 60-year old Mosotho woman working in South Africa as a domestic worker, who has a valid Lesotho passport and special exemption permit, shared her harrowing experience with this publication on condition of anonymity.

She told this publication that she was turned away from the gate of a clinic in Thembisa, South Africa, by Operation Dudula members after failing to produce a South African ID on August 4.

The woman had gone to the clinic to collect medication for high blood pressure, sweating, and swollen feet.

“They told me in the presence of the security officers at the gate that they wanted an SA ID but I showed them my passport and work permit,” she said. “But they told me that I will use a passport in Lesotho not there and that the work permit does not give me the right to access healthcare services.”

“I had gone to the clinic because my blood pressure was high. I was sweating profusely and my feet were swollen. Sadly, I had to go back without getting services,” she recalled. Her boss later took her to a private pharmacy where M578 was spent on consultation and medication.

She expressed her distress, stating that it would be hard for her to ever go to a health centre in South Africa again and she would be forced to buy medication instead.

“Every day is a struggle for us. I would not have afforded over M500 for medication. You can imagine if I have to spend that monthly because taking high blood medication is a journey for me,” noted.

Another domestic worker from Lesotho, ‘Mammita Sebofi, shared a similar experience at the same clinic in Thembisa. She took her two-year old daughter, who holds a South African birth certificate, to the clinic last Tuesday.

However, Sebofi was asked to provide a South African ID, which she didn’t have. “At the gate, I was asked to provide an SA ID which I couldn’t but showed the child’s birth certificate,” she said.

The group insisted that she needed to provide her ID or have the child’s father, who holds a South African ID, take the child to the clinic.

“We had to call my daughter’s father but he could not pick the call because of work, for about 30 minutes. My daughter had a fever, I stood there panicking waiting for her father to pick up the call until one of the group’s members asked me to pay M250 in order to go through.”

Faced with the demand, Sebofi had no choice but to pay the bribe. Fortunately, she had the money.

The Executive Director of Migrants Workers Association Lesotho, Lerato Nkhetše, told theReporter in an interview on Tuesday this week that they had received reports that Basotho and other foreign nationals were now being referred to ‘stations’ within health centres manned by gangs suspected to be Operation Dudula where they pay to avoid harassment. It is not clear where the monies received go to.

“This not only adds to their financial burden but also undermines their dignity and violates human rights and international laws,” Nkhetše said.

He noted that the harassment of Basotho in SA continues unabated despite a recent meeting between the health ministers of the two countries.

Nkhetše said Basotho’s plight highlights the need for greater accountability and transparency in the implementation of healthcare policies and agreements, he added.

His remarks come after the South African Human Rights Commission (SAHRC) last Friday approached the Durban High Court with an urgent application against Operation Dudula and another anti-foreigner movement March & March.

The Commission wanted the court to order these groups to stop people from accessing healthcare services in SA, citing that their actions were unconstitutional and unlawful.

They also wanted the court to prevent the vigilante gangs from demanding private persons from producing their IDs or any document demonstrating their right to be in the country.

The SAHRC cited the case of Addington Hospital in KZN, where members of these groups allegedly prevented individuals from accessing the facility upon failing to produce South African IDs.

This, despite the constitutional right of every person to have access to healthcare services, and in some instances, the right not to be refused emergency medical treatment.

The SAHRC stated that it had exhausted all reasonable avenues before approaching the Court, including engaging with the National Commissioner of Police and the Department of Health.

The Commission had directed correspondence to the two organisations, making it clear that their conduct is “unlawful, violates the constitutional rights of the affected persons, and poses a threat to public health.”

Despite this, the SAHRC claims that the South African Police Services (SAPS) and the Department of Health have failed to take effective steps to prevent the groups from unlawfully preventing patients from accessing healthcare services.

The Durban High Court however, ruled that the case was not urgent.

Nkhetše’s implored the governments of Lesotho and South Africa to work together to ensure that Basotho workers receive the healthcare services they need without facing undue hardship or exploitation.

Efforts to get comments from Operation Dudula members or government health officials this were not successful.

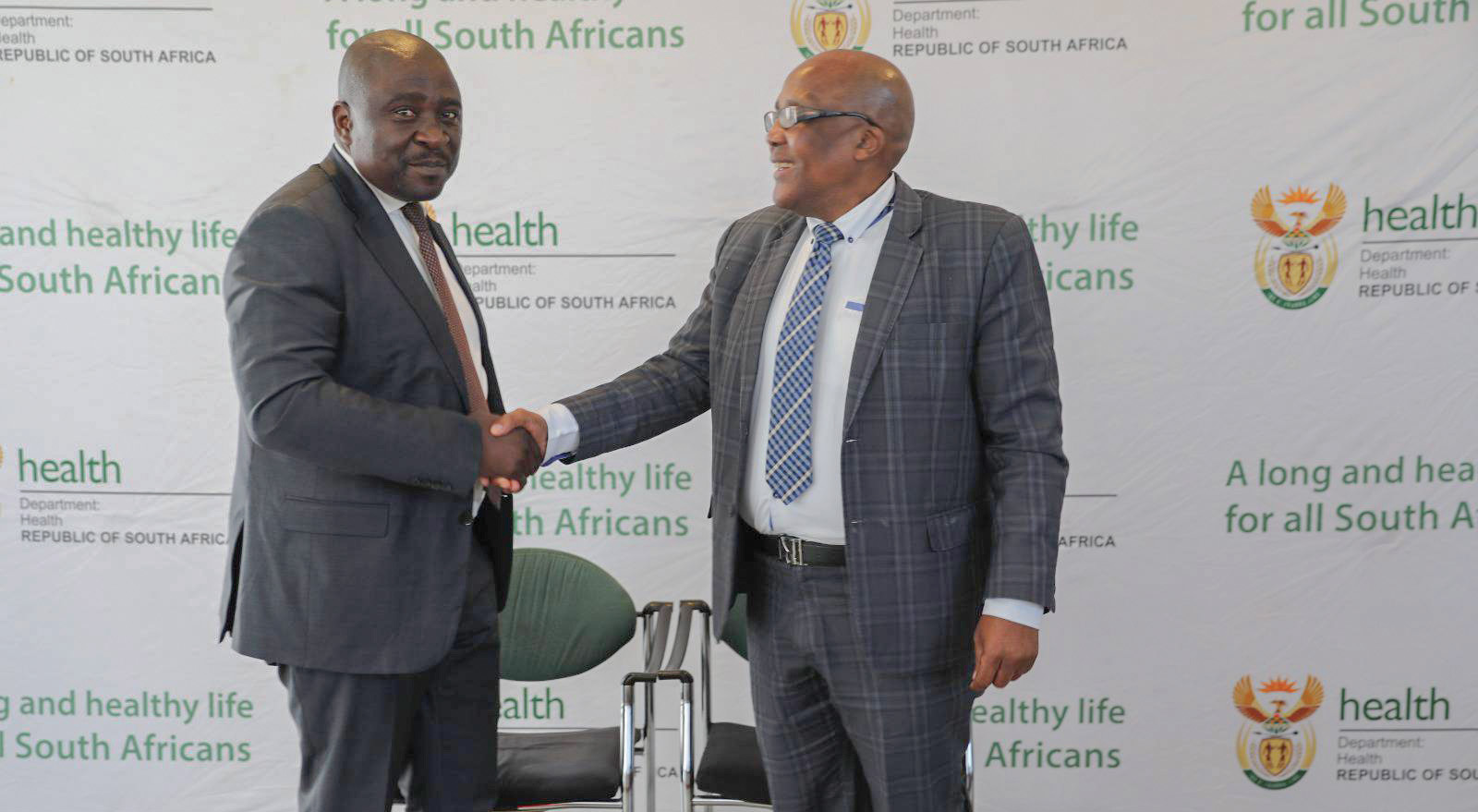

However, addressing media following their meeting, Mochoboroane said his SA counterpart Dr Aaron Motsoaledi had assured him that his country’s constitution prohibits denying healthcare to anyone, regardless of nationality or immigration status.

“We agreed that Basotho in South Africa should have equal access to health services, just as South Africans living in Lesotho receive such care without restrictions, while we work to formulate a permanent solution,” Mochoboroane stated.

He added that bitterness towards migrant workers in South African hospitals stems from locals feeling marginalised and perceiving that migrants are overburdening their limited healthcare resources.

In response to the growing concerns over access to healthcare, and following his meeting with Operation Dudula, Dr Motsoaledi had reiterated that no one should be denied medical care, regardless of their documentation status.

He emphasised that healthcare is governed by law, and it is essential to act accordingly to ensure that everyone receives the medical attention they need.

Dr. Motsoaledi stressed that acting outside the law, regardless of the intention, endangers lives and public health.

“Health belongs to everyone in line with the laws of the country. No one may be denied medical care regardless of their documentation status,” he stressed.

Lesotho to host SADCOPAC conference

7 days ago

Matekane mourns former Kenyan PM Odinga

7 days ago

Man seeks justice after assault at Ha Tsosane

10 days ago

Union blasts govt as Kao Mine faces shutdown

10 days ago

NUL students invent M200 heartbeat tracker

10 days ago

LNDC seeks Loti Brick liquidation

10 days ago