Correctional and health facilities conditions shocking

SHARE THIS PAGE!

The Sessional Select Committee on Pandemics says there is need for increased resources and personnel within correctional and health facilities to ensure adequate pandemic response across the country.

The committee said this during the ongoing inspection of correctional and health facilities nationwide. The visit comes amid growing concerns about the safety and well-being of inmates and health professionals, particularly during heath emergencies.

The inspection that commenced in July 1, covered Mafeteng Hospital, Mafeteng Correctional Service, Morifi Clinic, Quthing Correctional Service, Quthing Hospital, Qacha’s Nek Correctional Service, Ngoajane Clinic, Butha-Buthe Correctional Service, Leribe Correctional Service, St Rose Clinic, Berea Correctional Service, among others.

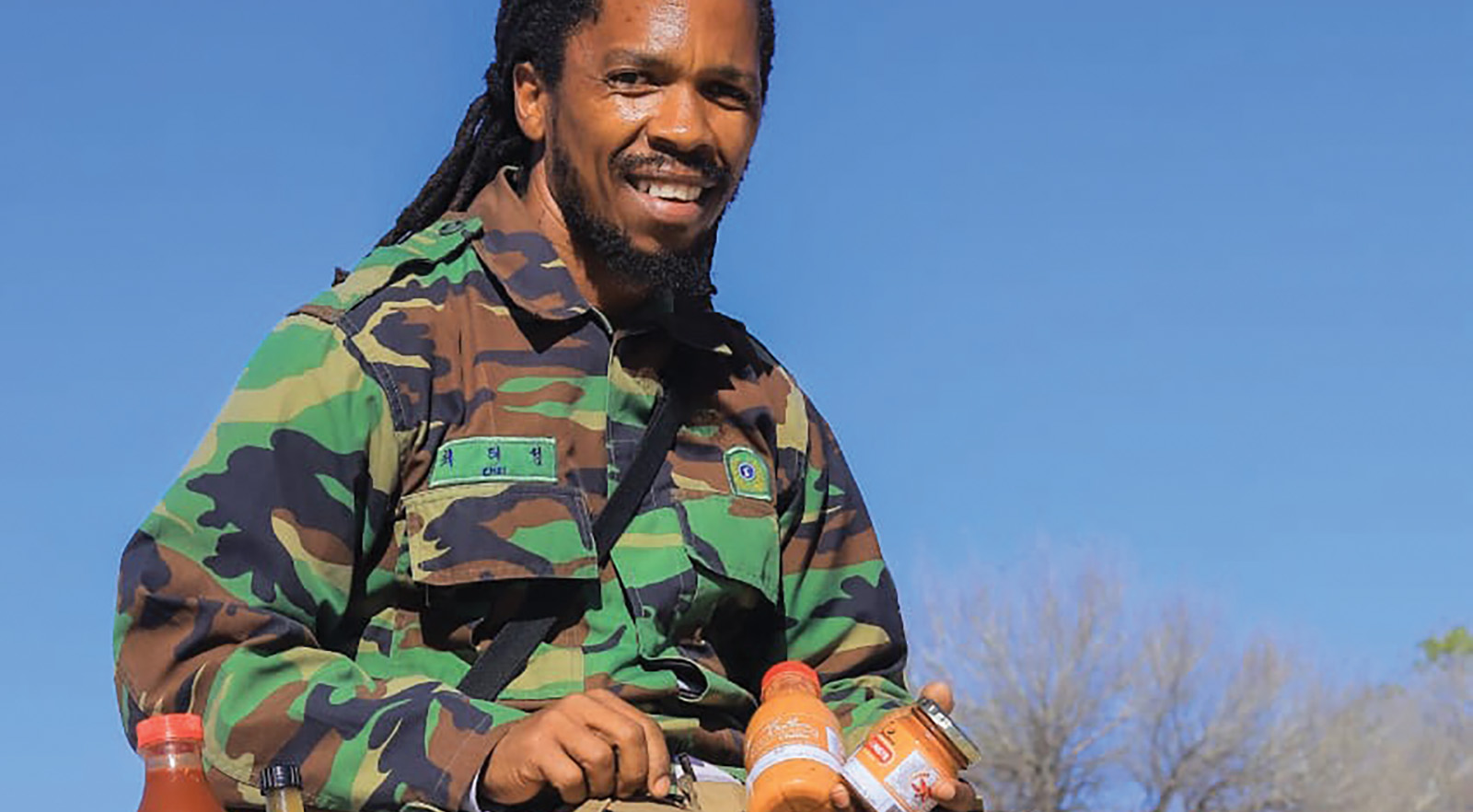

In this interview with theReporter’s ‘Mantšali Phakoana, the committee’s chairperson, Paul Masiu, provides an insight into the inspections’ findings and possible solutions.

What prompted the parliamentary committee to conduct inspections of health and correctional facilities nationwide?

The inspections on health and correctional facilities nationwide were prompted by insights gained from consultation meetings with the Ministry of Health and the Lesotho Correctional Service (LCS).

These meetings shed light on the daily operations, successes, and challenges faced by these institutions in managing chronic and pandemic diseases like HIV and TB, as well as the impact of the recent United States government executive orders on health services.

Following these consultation meetings, we decided to use an approach which we call ‘Thomas Approach’. We visited facilities to witness what is on the ground, so that when we debate and convince Parliament to allocate funds and enact laws based on what we witnessed.

What common challenges have you observed in both health and correctional facilities during the inspections?

One of the common challenges is that there are a lot of skilful, professional human personnel that have lost jobs in most of these facilities due to the US government orders on foreign policy. Some of them were provided by international organisations like Elizabeth Glaser Pediatric AIDS Foundation (EGPAF), and UNAIDs.

One example is Mafeteng Hospital where we witnessed a high number of pregnant women who had gone for services but there were only three nurses at work, who sometimes end up tired and moody because of overload, especially towards the end of the day.

We discovered that the three nurses assist more than 20 pregnant women daily and it is tiring. There is also lack of medication in most of the health facilities, within and outside correctional facilities. In some cases, we were told such medication is available at the ministry’s headquarters but there is no transport to deliver them throughout facilities in remote areas because some UN agencies that used to do such roles have stopped their operations.

The shortage of staff is evident not only in health facilities, but also in most correctional facilities, despite a high number of inmates.

At Quthing Correctional Service, they have machines that produce bricks but have turned into white elephants since no one is buying necessities such as cement and sand for inmates to manufacture bricks.

In addition, where inmates have done something for themselves and sold some produce, the money is taken to consolidated government funds and do not benefit them directly. Health professionals and correctional officers are demotivated due to poor morale, and poor communication with central government. They also complain about low salaries, lack of resources, and non-promotions even when higher positions are available.

How do you access the preparedness of these facilities in responding to public health emergencies?

Overall, we are not ready as a country. Many of our healthcare facilities lack necessary resources to effectively respond to health emergencies. For example, Mafeteng Hospital, which serves as a lifeline for its district, is forced to rely on just two oxygen gases, with one cylinder empty. The environment at the correctional facilities also doesn’t show readiness.

In one incident, the procurement process at the same hospital became a tragic hindrance in delivering lifesaving oxygen to patients. The bureaucratic red tape of seeking multiple quotations before awarding a contract to an oxygen supplier caused unacceptable delays, resulting in empty gas cylinders and, subsequently, grave consequences for those in urgent need of this vital gas.

Correctional services across several districts like Mafeteng, Mohale’s Hoek, Quthing and Qacha’s Nek are forced to rely on substandard pack homes for inmate housing, stated one source, expressing grave concern over the inhumane conditions. These pack homes, originally donated to assist the corrections system, have fallen into disrepair and no longer provide adequate shelter. During rainy days, they become dangerously damp and prone to leaks, posing a severe threat to inmates’ health and well-being.

The correctional facilities across several districts in Lesotho are plagued with a multitude of issues ranging from insufficient staffing to substandard living conditions. Some facilities have only one nurse, while others depend on acting staff who receive no additional pay.

Quthing and Qacha’s Nek correctional facilities are so abhorrent that even animals wouldn’t deserve to reside in them. The unsanitary conditions and lack of hygiene at these institutions are so poor that both inmates and the staff who care for them are negatively affected.

Inmates are forced to endure filthy conditions with inadequate hygiene facilities, leading to severe cases of infestation. The uniforms and blankets provided are in disrepair, and some inmates lack these essential items altogether.

Have you identified any systematic issues that contribute to the spread of diseases in these facilities? If so, what are they?

The lack of resources in many correctional facilities has led to the spread of infectious diseases such as HIV and tuberculosis (TB). Many inmates, especially those who have been abandoned by their families, are forced to rely on the kindness of others to meet basic hygiene needs like clothing and bathing supplies.

Unfortunately, this desperation sometimes leads to sexual exploitation and the transmission of diseases. Desperate for necessities like blankets, some male inmates have resorted to sexual favours in exchange for these basic items, resulting in increased HIV infection rates within the prisons.

Despite the country’s past success in battling HIV and TB, the lack of resources and support in Lesotho’s correctional facilities has reversed these gains. Inmates with HIV or TB who drop out of treatment due to the harsh conditions in prisons have contributed to the spread of these diseases. Additionally, the absence of non-governmental organisations (NGOs) that once supported the Ministry of Health in delivering medication to prisons has exacerbated the problem.

What best practices have you observed in some facilities that could be replicated in others?

Many inmates possess unique skills and talents that could be harnessed to not only improve their quality of life, but also to generate income for the facilities. For example, by developing goods or services that could be sold to the public, inmates could gain a sense of purpose and pride, as well as the financial means to purchase clothing and other necessities.

Some inmates have already taken the initiative, engaging in agricultural and animal husbandry practices within the facilities. For instance, by tending to chickens, and farming, inmates have demonstrated their ability to care for others while also producing goods and services that can benefit them directly. Others have pursued creative outlets such as handcrafts and artwork, fostering an entrepreneurial spirit among inmates and showcasing their hidden talents. These efforts, if supported and nurtured, could provide a vital source of income and personal fulfilment for inmates and the prisons.

What are the most significant gaps in healthcare delivery that you have observed in these facilities?

The lack of accessibility in remote areas compounds the already dire situation faced by many of Lesotho’s health facilities, particularly those like Morifi in Mohale’s Hoek district. The rough terrain makes it difficult for patients to reach the facility, contributing to a shortage of healthcare professionals who are reluctant to work in such environments.

One possible explanation for the lack of progress in addressing these issues may lie in the volatility of Lesotho’s coalition governments. Frequent changes in leadership have resulted in a lack of consistency and commitment in addressing the needs of correctional officers, health professionals, and inmates. The constant shift in priorities and policies has hampered efforts to find long-term solutions that can truly improve the situation within these facilities.

The Ministry of Justice and Law’s lack of a comprehensive policy to guide the management of correctional facilities has further contributed to the issues plaguing the system. Without clear guidance and regulations, inmates are left vulnerable to exploitation and abuse.

The current strategic plan, while a step in the right direction, falls short of addressing the systemic problems that perpetuate poverty and prevent inmates from achieving self-sufficiency.

How do you think the finding of this inspection can inform the policy decisions or reforms in the health and correctional sectors?

The findings of this inspection shed light on the dire conditions faced by inmates in Lesotho’s correctional facilities. These challenges require the commitment, will and support of MPs and the government to effect meaningful change.

What recommendations do you plan to make to address the challenges you have identified during the inspection, and what timeline do you envision for implementation?

There is need for increased resources and salaries for both correctional officers and health to give them motivation and willingness to do their jobs. It is also imperative for the government to increase the numbers health and correctional facilities, availability of medication, and more outreach by health professionals and community leaders, village health workers, support groups and MPs to communities to teach them how to take care of themselves.

One potential solution is to invest in the inmates themselves, by providing them with the necessary resources and training to produce goods and services that could benefit them and the prisons. For instance, uniforms could be manufactured by inmates, creating an opportunity for meaningful work and alleviating some of the financial burdens faced by the correctional facilities.

‘Tsunami’ hot sauce takes Lesotho by storm

9 days ago

Feuding neighbours fined for street brawl

12 days ago

TRC boss acquitted of sexual harassment

12 days ago

Foreign missions bleeding government purse

12 days ago

Breaking the silence on disability and GBV

14 days ago

Cultivating mushrooms using agricultural waste

15 days ago