WASCO opposes Mafeteng community lawsuit

SHARE THIS PAGE!

The Water and Sewage Company (WASCO) has submitted an affidavit opposing the legal challenge instituted by Mafeteng community, regarding the water crisis in the district.

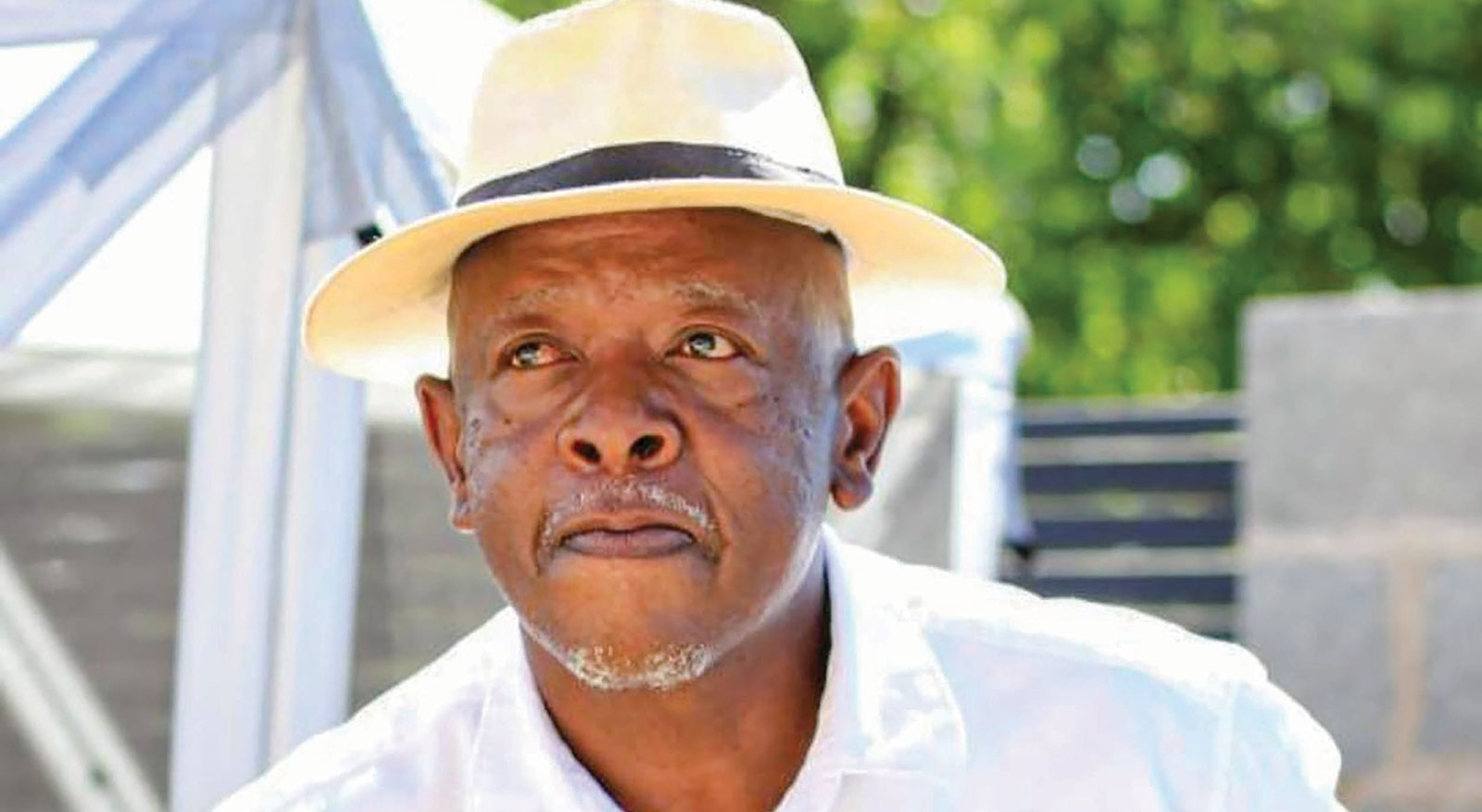

WASCO caretaker chief executive, Falla Seboko, filed the answering affidavit last Friday, refuting the community’s legal challenge and demanding that the application be dismissed with costs.

As the 13th respondent in the case, Seboko dismissed the urgency of the case, maintaining that the issues raised were not in the Constitutional Court’s jurisdiction.

The applicants who filed the case on behalf of others are: Khethisa Mokone, Ngoliloe Seotsanyane, Thoboloko Ntšonyane, Tefo Khunonyane and Seetsa Lesia.

The community had petitioned the court in an urgent application, arguing that their lack of access to clean water places them in imminent danger of ill health and eventual death. The water crisis in Mafeteng dates back to 2015.

The community cited multiple parties including WASCO, the Independent Electoral Commission (IEC), MPs for the following constituencies; Qalabane (Retšelisitsoe Matlanyane), Mafeteng (Moeketsi Motšoane),Mafeteng (Hlalele Letšaba), Thaba Phechela (Mohau Hlalele), Thabana Morena (Selibe Mochoboroane) and Phoqoane (‘Matankiso Tekane), ministers of natural resources, tourism and environment finance, health, local government and chieftainship, WASCO, Rural Water Supply (RWS), Mafeteng district administrator, as respondents in their lawsuit. They allege that the respondents have failed to address the water crisis and endanger the health and safety of residents.

Seboko argued that the applicants’ urgency claim was unwarranted as the water crisis had been ongoing for nine years.

He asserted that the residents’ decision to pursue legal action after such as a significant period of time undermined the legitimacy of their argument and warranted dismissal of their application.

Seboko further submitted that applicants do not have loco standi and or the capacity to institute the matter before the court.

He noted that the right sought to be enforced by the community are socio-economic non-justiciable rights, not enforceable by a court of law. This application ought to be dismissed for lack of loco standi on the part of the applicants, he contended.

Furthermore, Seboko argued that the Constitutional Court did not have the legal authority to hear the case, citing Section 25 and 35 of the Constitution of Lesotho.

Seboko addressed the merits of the case, stating that WASCO had consulted the residents of Mafeteng before using an alternative water source. According to him, the company’s actions were not only within the bounds of the law but also performed in consultation with local stakeholders.

His answering affidavit refuted the allegations that WASCO’s actions violated residents’ property rights or endangered the environment.

“It is not correct that WASCO’s conduct of piping water from the alternative water sources violates the right to property and is hazardous to the environment and well-being as envisaged under Section 14 and 17 of the Constitution of Lesotho, read with Section 31, 61 and 95 of the Water Act, 2010 and Environment Act, 2008 as will be here under demonstrated,” Seboko wrote in his answering affidavit.”

He also refuted the community’s demand for WASCO to manage and maintain its water sources more efficiently, claiming that the request violated the Lesotho Constitution.

According to him, the community’s request for a mandatory order demanding such management would violate Section 25 of the Constitution, which safeguards public policy principles and restricts courts’ jurisdiction on matters of financial feasibility and development capacity.

Seboko argued that the rehabilitation of the dam was ultimately dependent on the government’s financial capacity and as such, could not be compelled by a court order.

He reasoned that as a constitutional matter, the court was limited in its ability to enforce such a costly undertaking, regardless of the damage suffered by the community.

Seboko added that the case does not present a constitutional issue but rather falls under the purview of ordinary courts, thus invalidating the community’s chosen avenue for legal redress.

He argued the case was beyond the case was beyond the Constitutional Court’s jurisdiction asserting that the issues raised by the community were subject to limit of the economic capacity and development in the country and therefore could not be enforced by the court.

Seboko cited Section 25 and 35 of the Constitution of Lesotho as the basis of his claim, maintaining that these provisions safeguard the principles of public policy in the country, thus the court lacked the authority to adjudicate over the matter.

The residents want the court to order the IEC to establish guidelines to ensure that political candidates do not make unconstitutional and exaggerated election manifestos.

They also seek a declaration that the failure of government, by itself, or WASCO and Rural Water Supply (RWS), to maintain dams, store adequate water and deliver clean water to them violates the people’s right to access to water.

They want the government to rehabilitate the following lakes and dams: Rasebala, Ha Maoela, Thotaneng, Ha Montoeli, Ha Rakhasapane, Boluma-Tau, Raleting, Tšakholo, Tša-Letima, Luma, Sampokane and Ha Mohlehli.

Law Society Bill in Parliament

15 hours ago

Metropolitan unveils new innovations

18 hours ago

Judiciary in crisis: top judge

2 days ago

Payment blunder hits DMA workers

2 days ago

Global uncertainty to impact Lesotho economy

2 days ago

NUL to celebrate 80th anniversary

2 days ago

RSL destroys illicit tobacco products

2 days ago

Part 2 of cannabis expo around the corner

3 days ago

Abortion reform sparks healthcare debate

3 days ago

Govt reacts to US tariff increase

5 days ago